Bōdhisattva Path and World Peace

发布: 2017-06-15 19:50:00 作者: Toronto Mahavihara Buddhist Center Ahangama Rathan 来源: 本网讯

Exploring the ideology and application of Bodhisattva Path and its impact on World Peace

Toronto Mahavihara Buddhist Center(多伦多大寺佛教中心) Ahangama Rathanasiri

Formation of Buddhist Traditions

The Mahāyāna School of Buddhism that emerged from the original dispensation established by the Gauthama Buddha is believed to have originated from the Mahāsāṃghika Sect. Until three months after the demise of the Buddha there was no division among the Sangha community. However there arose a necessity of resolving certain prevalent issues and a decision was made to call a Sangha Council under the leadership of Arahant (Fully Enlightened) Maha Kashyapa. This Sangha Council was held at the entrance to the Saptaparni Caves in the Indian city of Rajagaha (now Rajgir) in the presence of 500 Arahants circa 400 B.C.E. Questions relating to monastic discipline (Vinaya) were dealt with by Arahant Upali and those relating to the doctrine (Dhamma) were handled by Arahant Ananda. In addition a systematic process was created for the oral transmission of the scriptures of the Monastic Discipline and the Doctrine so that they will be bequeathed to the future generations in perpetuity.

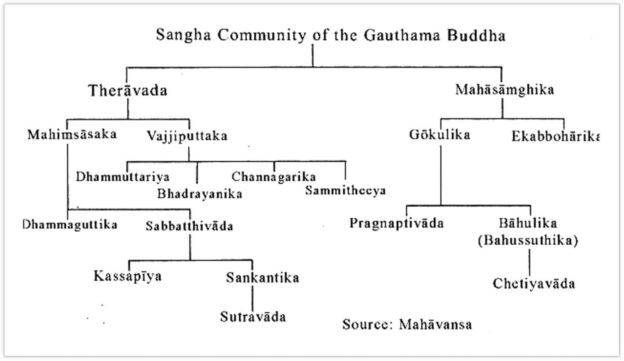

Figure 1 – Formation of Buddhist Traditions

About 100 years after the First Council, the Second Council was convened in the city of Vaishali (in Bihar Province, India), with the attendance of seven hundred Arahants under the leadership of Arahant Sabbakami, mainly to consider the dispute caused by the ten monastic discipline reformative points adopted by a group of monks known as Vajjiputtaka. The noble Sangha Community of the Gauthama Buddha that remained united up till now began its schism ① after the Second Council. According to a source like Deepavansa, the popular belief is that a new sect called Mahāsāṃ ghika was created by the break-away monks of the Vajjiputtaka group who called another Council of their own, in response to the censure of the “Ten Points” by the Second Council. In a Chinese version of the Mahāsāṃ ghika Disciplinary scripture, however, it is stated that the Mahāsāṃghika sect acknowledged the violation of its discipline by the above “Ten Points”. In the documents belonging to Sammithiya Sect, it has been recorded that during the period between Second and Third Councils, 5 attributes of an Arahant have been submitted by a monk by the name of Bhadra. At a separate Sangha Council conducted under the sponsorship of the King of Patali Putta, those monks who accepted these five attributes as valid, formed the Mahāsāṃghika group. Those 5 attributes of an Arahant are:

1.An Arahant may have lust.

2.An Arahant may have delusion.

3.An Arahant may be sceptical.

4.An Arahant must be enlightened by another person.

5.An Arahant may achieve enlightenment by pronouncing a certain word.

The negative attributes stated above have degraded the enlightened disposition of an Arahant who has in reality extinguished all attachments to the world and terminated the cycle of birth and death by self perseverance. A discussion on this matter can be found in the “Parihāni Kathā” chapter in “Kathāvattu Pakaranaya”, an Abhidhamma book belonging to Theravāda School. It can be assumed that the concepts depicted in these beliefs may have formed the foundation on which the Mahāyāna Tradition was built and its beginning can be seen in the Mahāsāṃghika ideology. Its basic principles consist of denigrated position of an Arahant, amplified image of the Bodhisattva and the exaggerated super-mundane qualities of the Buddha.

With the separation of the Mahāsāṃghika monks from the main stream of the Sangha Community, the remaining monks came to be known as the Theravada or the doctrine of the Elders. With time, various other sects were born in total 18, as a result of disputes caused by differences in opinions with regards to the nature of the Dhamma, super-mundane status of the Buddha, concept of non-soul, theory of self etc. Birth of a large number of sects during this period has been seen as a favorable sign of a vibrant doctrine. Professor M. B. Baruwa of the University of Calcutta, India has stated that the appearance of conceptual differences and diverse sectarian groups was a sign of progressive development. The Buddhist Doctrine did not stagnate nor did it stay dormant, but was alive to the changing social and physical environments and retained its tenacity in continuously expanding its horizon.

Emergence Mahāyāna School and the concept of Bodhisattva

The word “Mahāyāna” has not appeared in any Buddhist literature prior to the Fourth Council which was administered during the period of King Kanishka (c 1 century AD). For the first time it appears in the Mahāyāna Shraddothpāda Sutta (Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna) authored by Poet Ashvagosha (c 1 century AD). Mahayanists do not believe in 3 vehicles ②; the only path that leads to the realization of the Truth is by being a Bodhisattva and then attaining enlightenment. Accordingly all human beings should be Bodhisattvas. The vehicle of Bodhisattva or BuddhaYāna is the one and only route leading to liberation. Because this vehicle is the singular path to emancipation for the living beings, it is known as “Great Vehicle (Mahāyāna)”.

Quoting from the Commentaries of the Theravada School “Bodhi vuccati catūsu maggesu ñāṇaṃ” (See Sāriputtasuttaniddesa, Mahāniddesa, Aṭṭ hakavagga), “bodhi” means the knowledge of the four-fold path or the realization of Nirvāna. In general sense of the Theravāda Tradition, Bōdhisatta means a noble person who has received a firm prediction of becoming a future Buddha (niyatha vivarana) from another Buddha. His first and foremost goal is to strive for the full enlightenment by fulfilling ten perfections③ which may take unimaginable length of time and unimaginable number of births. Analyzing the word, “satta” which is derived from Pāli root “sañja”, means “attachment”. Subjecting it to Pāli declension, “sattō” “āsaththō”, “visattō” respectively mean “one who is attached”, “one who is mildly attached” and “one who is extraordinarily attached”. However, the true quality of a Bodhisattva does not become apparent by assigning “attachment” to the meaning of “satta”. Therefore the Mahāyāna Tradition adopted the word Bodhisattva④ to connote a being who is destined to attain full enlightenment. Similar to a seed that contains an embryo for germination at a later stage, Bodhisattva possesses all qualities required for subsequent enlightenment. It would be more appropriate to describe such a person as one who is endeavoring to attain full enlightenment or one who has made it his sole aspiration. The Sanskrit word satva can be interpreted as “human values”. According to P.T.S Dictionary, Bodhisatta is defined as “bodhi-being i.e. a being who is destined to attain fullest enlightenment or Buddhaship. A Bodhisatta passes through many existences and many stages of progress before the last birth in which he fulfills his great destiny”.

The primary purpose of a Bodhisattva is to show a way for the beings to escape from the tentacles of Samsāra. Referring to the famous Mahāyāna Buddhist Text, Bodhicaryāvatāra⑤ (A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life), the Bōdhicitta is the singular wish of a Bodhisattva integrated with boundless compassion and wisdom, with a strong determination to realize the Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings. It is also the one and only path to the Buddhahood. Foremost characteristic of Bodhisattva is compassion and wisdom. At the instant of generating a Bōdhicitta to become a Bodhisattva, he makes a vow to himself thus:

I will delay my awakening until all sentient beings living in every realm of the universe, whether they be egg-born, womb-born, water-born or spontaneously born; whether they are far or near, slim or obese, gross or subtle, large or small, are liberated from the Samsāra.”

In order to give a sensible meaning to the infinitely boundless compassion that would be radiated to all the sentient beings in the three realms of the universe, that compassion should invariably be devoid of the perception of self. In other words the compassion should be extended with wisdom built on the understanding of the real nature of the conditional phenomena, seeing all tangible as well as abstract forms such as personality, beings, self, aggregates, fundamental elements, sense-bases etc. as void or illusions. Further all phenomena should not be considered as independent, or unconditioned. In terms of Madhayamaka⑥ philosophy all phenomena are inter-dependent and inter-related thus giving rise to the emptiness of substance as a result of the absence of inherent existence; herein all beings as well as phenomena are without self-essence. According to traditions of asceticism, wisdom is considered as the ability to see all beings, life, self, phenomena etc. as illusions of the mind. The propagation of boundless, altruistic compassion over all living beings without any exclusion is possible only through self-less perception of the vacuous and illusory nature of the world. According to Mahāyāna Philosophy if a person is embodied with the perceptions of personality, self, being, life etc., that person is not a Bodhisattva; a Bodhisattva should be in full realization of the true nature world as it is and that insight is known as wisdom. Discernment of the true nature of the phenomena alone can achieve the infinite compassion over all the living beings. If a Bodhisattva has not eliminated the notion of the existence of an entity, he may be subject to defilements of attachments and clinging; he should also be devoid of the perception of himself. Failure in this respect is a failure of his own goals. On the other hand he should also eliminate the perception of the existence of other beings; if not he fails in the deliverance of others. In short Bodhisattva is one who is engrossed with two fundamental functions: liberation of himself and the liberation of others.

Mahāyāna Buddhist Text, Bodhicaryāvatāra referred to in the previous page describes the infinite nature of the compassion possessed by a Bodhisattva towards all living beings, in the following terms: “Bodhisattva is not hesitant to donate his hands and feet of the body even to those who offended him; he would even enter the Avichi hell to get them released from there. He would altruistically sacrifice all his lives, movable as well as immovable possessions and all the wholesome kammas accrued through the Samsāra for the benefit of all living beings. His sole aspiration is that as far as the sky extends, as far as the universe expands, that far will his existence endure the suffering of the people.”

In the Kakacupama Sutta (The Parable of the Saw) in the Majjhima Nikāya of the Sutra Pitaka, the Buddha exhorted his monks the extent to which the love should be radiated in the following passage⑦:

“Monks, even if bandits were to savagely sever you, limb by limb, with a double-handled saw, even then, whoever of you harbors ill will at heart would not be upholding my Teaching. Monks, even in such a situation you should train yourselves thus: 'Neither shall our minds be affected by this, nor for this matter shall we give vent to evil words, but we shall remain full of concern and pity, with a mind of love, and we shall not give in to hatred. On the contrary, we shall live projecting thoughts of universal love to those very persons, making them as well as the whole world the object of our thoughts of universal love — thoughts that have grown great, exalted and measureless. We shall dwell radiating these thoughts which are void of hostility and ill will.' It is in this way, monks, that you should train yourselves.

“Monks, if you should keep this instruction on the Parable of the Saw constantly in mind, do you see any mode of speech, subtle or gross, that you could not endure?”

“No, Lord.”

“Therefore, monks, you should keep this instruction on the Parable of the Saw constantly in mind. That will conduce to your well-being and happiness for long indeed.”

Above paragraphs amply clarifies the extent of the compassion possessed by a Bodhisattva. Mahāyāna School very rightly finds fault with Theravādins who seek individual self-emancipation while rest of the beings in the universe undergo immense suffering in the Samsāra. According to the Mahāyāna School, Theravādins do not practice compassion.

Mahāyāna School believes that the Bodhisattvas who have eliminated the five hindrances and fully developed the compassion and wisdom are competent enough to guide other living beings from the fetters of Samsāra. They are in a state that would make it possible for them to attain Nirvāna at any time they desire. There is no requirement for them to be isolated in a forest and develop meditation under a tree or in an empty location to realize enlightenment; since they have already seen the reality of all phenomena (emptiness), it makes no difference whether it is a noisy crowded place, empty place or a forest.

The Bōdhicitta (awakening mind) and the Bodhisattva are two fundamental factors in the Mahāyāna doctrine. Mahāyāna scriptures indicate that the citta (mind) can be analyzed in three categories as follows:

(i)Worldly Mind

(ii)Bodhisattva Mind

(iii)Bōdhicitta (awakening mind)

Worldly mind is constantly polluted by the defilements caused by the egoistic nature of the human beings. Therefore it eternally wanders in Samsāra being subject to birth, aging, disease and death.

In contrast the Bodhisattva Mind having understood the drawbacks of the worldly mind strives to attain a sublime state of enlightenment, by eradicating defilements, fulfilling perfections and accruing wholesome virtues.

The ultimate mind of an exalted being who is devoid of all forms of defilements and who has realized the supreme state of Buddhahood having totally eradicated the suffering is the Bōdhicitta. The Bōdhicitta is strictly a quality of a Self Enlightened Buddha (Sammā Sambuddha). The Bōdhicitta as well as its mental functions transcend the human world.

According to the doctrine of Mahāyāna, the seeds of Bōdhicitta reside in all sentient beings impending to be awakened. It becomes fully blossomed only in the Buddhas. While it is in a dormant state, there are four ways it can be stimulated:

1. Contemplating on the Fully Enlightened Buddhas.

2. Contemplating on the suffering in Samsāra.

3. Contemplating on the various causes of suffering that afflict the beings.

4. Contemplating on the qualities of the Fully Enlightened Buddhas.

When a being develops Bōdhicitta he also develops, along with it, the compassion and wisdom. From that instant he becomes a Bodhisattva. In the state of Bodhisattva he gains a special feature of the associated mental functions that causes him to make a vow to himself that he will delay the attainment of Nirvāna until all beings living in the three realms: realm of sensual pleasure (kāma lōka), realm of form (rūpa lōka) and formless realm (arūpa lōka), are absolved from the grips of the Samsāra. The vow Bodhisattva makes thus is a unique characteristic of the Bōdhicitta.

Concept of Bōdhisatta in the Theravāda Tradition

Turning back to the teachings of the Theravāda school, the objective of a Bōdhisatta who is aspiring to be a Fully Enlightened Buddha is to seek emancipation for himself first and then show others the path to do it. The sage Sumedha who had already developed all necessary requisites to attain arahantship, received a pronouncement from the Dipankara Buddha that he will become a fully enlightened Buddha in the future by the name of Gauthama. The sage Sumedha then thought thus:

Kiṃme aññātavesena, dhammaṃ sacchikatenidha;

Sabbaññutaṃ pāpuṇitvā, buddho hessaṃ sadevake.

(Sumedhapatthanākathā, Buddhavaṃsa, Khuddakanikaya)

Meaning:

What use it will be if I realize the Dhamma while remaining unknown.

Having become omniscient I will liberate whole world including heavenly beings as a Buddha.

The being who receives a pronouncement from a Buddha that he will become a Buddha at a future time will commence perfecting Ten Perfections forthwith. Such a being is known as a Bōdhisatta in the Theravāda Tradition.

Ten Stages (Bhūmis) in Mahāyāna Tradition

Corresponding to the Ten Perfections mentioned above in the Theravāda

Tradition, Mahāyāna specifies Ten Stages (Bhūmi) as the path to awakening; but they are not similar in performance. All Bodhisattvas should perfect the Ten Stages (Bhūmi) to attain full enlightenment. The Mahāyāna Tradition also has Perfections, six in number, that come after accomplishing the seventh Stage (Bhūmi) known as Dūrangama.

Different sources in Mahāyāna School present diverse interpretations of the concept of the Ten Bhūmis. The Mahāvastu, a Text of the early Buddhism, differs considerably from the descriptions given for the Ten Bhūmis in the Dasha Bhūmi Sutra and Avatamsaka Sūtra. Another entirely different explanation appears in the Bōdhisatta Text in which only seven Bhūmis are enumerated. In the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra an additional Bhūmi, namely tathāgata Bhūmi, has been added making it eleven Bhūmis. In a Text known as “Dharmasangrahaya” its author, Har Dayal has referred to two additional Bhūmis known as Hirupamā and Gnānawathi. Though such varying interpretations are present in Mahāyāna literature, it is generally accepted that Mahāyāna School acknowledges only Ten Bhūmis as given in the Dasha Bhūmi Sutra.

The Ten Bodhisattva Bhūmi are the ten stages on the Mahāyāna Bodhisattva's path of awakening. The Sanskrit term Bhūmi literally means “ground” or “foundation”. Each stage represents a level of attainment, and serves as a basis for the next one. Each level marks a definite advancement in one's training that is accompanied by progressively greater power and wisdom.

The bhūmis are subcategories of the Five Paths (pañcamārga):

1.The path of accumulation (saṃbhāra-mārga). Persons on this Path:

1) Possess a strong desire to overcome suffering, either their own or others;

2) Renounce the worldly life.

2.The path of preparation or application (prayoga-mārga). Persons on this Path:

1) Start practicing meditation;

2) Have analytical knowledge of emptiness.

3.The path of seeing ( darsana-mārga). Persons on this Path:

1) Practice profound concentration meditation on the nature of reality;

2) Realize the emptiness of reality.

4.The path of meditation ( bhāvanā-mārga). Persons on this path purify themselves and accumulate wisdom.

5.The path of no more learning or consummation (aśaikṣā-mārga). Persons on this Path have completely purified themselves.

Ten Stages (bhūmis)

The Avataṃsaka Sūtra refers to the following ten bhūmis:

1.The first bhūmi, the Very Joyous. (sudurjayā) in which one rejoices at realizing a partial aspect of the truth;

2.The second bhūmi, the Stainless. (vimalā) in which one is free from all defilement;

3.The third bhūmi, the Light-Maker. (prabhākarī) in which one radiates the light of wisdom;

4.The fourth bhūmi, the Radiant Intellect. (arciṣmatī) in which the radiant flame of wisdom burns away earthly desires;

5.The fifth bhūmi, the Difficult to Master. (sudurjayā) in which one surmounts the illusions of darkness, or ignorance as the Middle Way;

6.The sixth bhūmi, the Manifest. (abhimukhī ) in which supreme wisdom begins to manifest;

7.The seventh bhūmi, the Gone Afar. (dūraṃgamā ) in which one rises above the states of the Two vehicles;

8.The eighth bhūmi, the Immovable. (acalā) in which one dwells firmly in the truth of the Middle Way and cannot be perturbed by anything;

9.The ninth bhūmi, the Good Intelligence. (sādhumatī) in which one preaches the Law freely and without restriction;

10.The tenth bhūmi, the Cloud of Doctrine., (dharmameghā) in which one benefits all sentient beings with the Law (Dharma), just as a cloud sends down rain impartially on all things.

The Ten Stages (bhūmis) and The World Peace.

As stated above Mahāyāna doctrine basically differs from that of Theravāda in the way the final goal is reached. The Mahāyāna Bodhisattva's immediate desire is to guide the rest of the beings to liberation before he himself attains Nirvāna because of the infinite compassion he developed towards others. Unlike the Theravāda doctrine, Mahāyāna rejects the ideal of release from the suffering in Samsāra through individual effort and promotes the idea of universal liberation of all beings by a Bodhisattva. This concept has an enormous impact on the world peace that everyone is seeking at the modern times.

The progressive path to world peace can be seen in the ten stages (bhūmis) of Bodhisattva's path to awakening. Many of today's international disputes arise from the fact that the true situation of the prevailing conditions is deliberately ignored and selfish agendas implemented for individual benefit. If a proper assessment of the ground situation is made it is possible to find an unbiased solution through compassion for the others. The remedy to this status is given in the first bhūmi in which one initiates search for the truth. Thereafter he advances freeing himself from defilements and gaining wisdom with which he destroys all earthly desires. The wisdom so gained leads to removal of the illusions one carried so far and the supreme wisdom of perceiving the absence of inherent existence, manifests forthwith. In the seventh bhūmi one engages in the development of high levels of mental absorptions passing beyond mundane and super mundane states. The eighth bhūmi is an extremely decisive stage in that the completion of this level makes the progression of the Bodhisattva irreversible and he is destined to eventual full enlightenment. It is during this stage that the Bodhisattva accomplishes the six Perfections:

1. Perfection of Generosity

2. Perfection of Morality

1. Perfection of Patience

2. Perfection of Energy

3. Perfection of Meditation

4. Perfection of Wisdom

The ninth bhūmi is expanding Bodhisattva's already developed intelligence in order to master all aspects of the doctrine enabling him to teach it to the humans. In the final stage of tenth bhūmi the Bodhisattva completely eradicates the subtlest traces of afflictions and devotes himself to the propagation of the Dharma like a cloud that pours rain on the earth.

From the foregoing account of the ideal of a Bodhisattva it is shown that his one and only desire is to bring the rest of the beings to enlightenment. Until such time that his aspiration is fulfilled he too will sojourn in the Samsāra even though he has attained enlightenment. He has developed all the necessary qualities and tools to guide the sentient beings out of the bonds of Samsāra and he will pass through life after life for this purpose. The global challenges faced by the humanity today are made by the man himself who does not realize the value of spiritual development. The resolution for these challenges also lies squarely in the hands of the mankind. In this regards the Bodhisattva ideal plays a critical role in transforming the human attitudes in line with the doctrine of Mahāyāna.

References:

① See Figure 1.

② According to Theravada Tradition, the enlightenment can be achieved in three ways i.e as an Arahant, as a Pacceka Buddha or as a Sammā Sambuddha. They are referred to as vehicles (Yanas)

③ Ten Perfections: generosity, virtue, renunciation, discernment, persistence, endurance, truth, determination, good will, and equanimity.

④ Note the spelling difference in the two words: Bodhisattva (Mahāyāna) and Bōdhisatta (Theravāda)

⑤ Also known as Bodhisattvacharyāvatāra was authored by a Buddhist monk named Śhāntideva of The Nālandā Monastic University of India in c. 700 A.D.

⑥ Mahāyāna school of philosophy founded by Nagarjuna. According to Madhyamaka all phenomena (dharmas) are empty (śūnya).

⑦ Courtesy: http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/mn/mn.021x.budd.html.